Goldfish Syndrome

Indefinite Hiatus

Goldfish remains an unfinished chapter, a project we were deeply passionate about. We were riding high on the momentum of a successful demo. But right after that peak, we hit a sudden wall: one of our core developers decided to quit the project.

It was my first time facing a team breakup. I didn't know how to handle the loss of a key pillar, and the creative momentum shattered. Currently, the project is on indefinite hiatus.

Status: Indefinite Hiatus · Tools: Unity, Custom Internal Tools

Roles: Programmer / Designer / PM

Project Overview

But a paused project is often the best teacher. Looking back, the time we spent on Goldfish was not wasted time. It forced us to confront advanced challenges in narrative design, technical pipelines, and team dynamics. We walked away with a treasure trove of design insights that have shaped how I approach development today.

Goldfish is a node-based visual novel designed with three main chapters.

For Chapter 1, we took a bold stance: it is strictly a Narrative-Driven (or 'Experience-First') chapter. Because of this, structure and pacing became our absolute priorities. To ensure the emotional delivery landed exactly how we intended, we inevitably had to make a difficult trade-off: sacrificing Player Agency.

To put it bluntly, the presentation of this chapter leans heavily towards a traditional Visual Novel, rather than a highly interactive game. We guided the player's hand to tell a specific intro story.

In Chapter 2, we shatter the linear structure introduced a new core mechanic: Honda's Notebook. Since the player assumes the role of Honda (the psychologist), this notebook becomes their tool to directly manipulate the narrative world. The game also begins to bleed into reality here, characters start to gain awareness, eventually becoming able to see and interact with the UI itself.

Everything culminates in Chapter 3. This is where the Meta-fictional elements are fully revealed, leading to an emotional crescendo. The logic established in the previous chapters collapses to make way for the raw emotional core of the story.

Design Pillars

Design Pillar 1: The Meta-Element as a Narrative Weapon

In Goldfish, our approach to Meta-elements centers on one goal: The Violation of Expectations.

To achieve this, we designed a two-step psychological trap:

Step 1: Establishing the 'Safety Zone'

First, we condition the player. Through hours of gameplay, we establish the UI as a 'sterile' environment. It is invisible to the characters and responsive only to the player. It becomes the player's Magic Circle, a place of absolute control and safety.Step 2: The Intrusion (Natasha's Agency)

Then, we break that trust. We don't just use cheap glitches. Instead, late in the game, we reveal a terrifying truth: a specific character, Natasha, has been accessing the UI alongside the player. She hasn't just been watching; she has been using the interface to manipulate the story's direction to suit her own desires.

The Expressive Goal:

By giving an NPC access to system-level tools, we aim to convey two themes:

- Inescapability: If even the 'Menu' isn't safe, then the horror is omnipresent. The Meta-element becomes a metaphor for a deterministic fate.

- The Bleeding Boundary: The UI serves as the thin membrane between the 'Ordinary' and the 'Extraordinary.' By allowing Natasha to cross this line, we create a two-way influence: the player affects the game, but the game (Natasha) actively fights back to affect the player's experience.

Design Pillar 2: The Psychoanalytic Lens

To create truly multi-dimensional characters, we turned to Psychoanalysis. But we didn't want to just dump theory on the player; we needed a vessel.

That vessel is our protagonist, Honda.

Honda as a Narrative Tool:

Honda is designed as a professional researcher with a heavy academic background. We utilize his 'Clinical Gaze' to create a sharp contrast against the rest of the game world:

- Tonal Contrast: While other characters speak in colloquial, emotional, or chaotic language, Honda dissects events with academic detachment.

- Perspective Contrast: In a genre where protagonists usually panic, Honda attempts to rationalize the irrational.

This makes Honda more than just a main character; he is our primary instrument of expression. His calm, analytical voice highlights the madness of the world around him, creating an uncanny valley between 'Logic' and 'Horror'.

The Ultimate Payoff: The Collapse of Reason

Crucially, this construction serves a darker purpose.

We built Honda as the unshakeable pillar of logic for one reason only: to break him.

By forcing the player to rely on his rationality throughout the game, we ensure that when we finally destroy him in the end, the impact is not just emotional—it is catastrophic. The fall is infinitely more painful because he fell from such a height of arrogance.

Design Pillar 3: The Existential

Core Concept: While Goldfish features distinct character arcs, they are all tethered to a single "Mother Motif": Existentialism.

We treat the narrative as a prism—the white light of "Human Existence" hits the prism and refracts into different colors, each represented by a character.

The Structure: We explore the terror of the "Human Condition" through three specific variations:

- Isolation: The struggle to define oneself (Natasha).

- Domestication: The struggle to fit into society (Yori).

- Destruction: The struggle to find meaning in endings (Tumugi).

Our goal is to ensure that every personal conflict in the game echoes this larger philosophical debate.

Design Obstacles

Obstacle 1: The Trap of Premature Agency

The Problem:

In our early iterations, we gave players full access to game mechanics and decision-making right from the start of Chapter 1. We thought this would make the game feel "interactive" immediately.

However, we soon discovered a fatal flaw: The players were influencing the world before they understood it.

Because they hadn't grasped the rules or the stakes of the Goldfish universe yet, their choices were essentially random guesses. When these choices led to tragic consequences later in the story, players didn't feel a meaningful sense of responsibility. Instead, they felt a confusing sense of "Unearned Guilt." They felt blamed by the narrative for mistakes they didn't know they were making. It felt less like a tragedy and more like a trap.

To fix this, we made a counter-intuitive decision: We stripped away the player's agency in Chapter 1.

- Removal of Choice: We converted Chapter 1 into a strictly linear experience.

- Pacing Adjustment: We significantly shortened the chapter to keep the momentum tight.

- Establishing the Baseline: Instead of asking players to act, we focused entirely on establishing the 'Normalcy' and Emotional Anchors. We used this linear space to firmly cement Honda's psychoanalytic perspective and the "Safety Zone" of the UI.

By forcing the player to observe first, we ensure that when they do get the power to change things in Chapter 2, they fully understand the weight of the gun they are holding.

Obstacle 2: The Controversy of Forced Complicity

The Scenario:

In the Prologue, we designed a sequence where the player controls Natasha during the traumatic event of losing her brother.

Crucially, this wasn't a branching path. We implemented a "Forced Choice": the player must perform the action that leads to this tragedy.

There is no way to save him.

The Internal Conflict:

This specific design sparked a heated debate within our team.

Some argued it was "unfair" or "cruel" to force the player's hand. It felt like railroading.

We questioned if it was right to make the player feel responsible for an outcome they couldn't prevent.

The Decision: Showing the Weight of the "Magic Stick"

Ultimately, we decided to keep it.

Why?

Because we needed to demonstrate the sheer, terrifying power of the tools the player holds. We wanted to show that the "Magic Stick" (the player's ability to influence the narrative) is not a toy—it is a weapon. It has consequences.

By forcing the player to click, we actuate a sense of Complicity.

- If we just showed a cutscene, the player is a witness.

- By making them interact, the player becomes an accomplice.

It was a painful design choice, but it was necessary to establish the game's dark tone: You have power, but power doesn't always mean salvation.

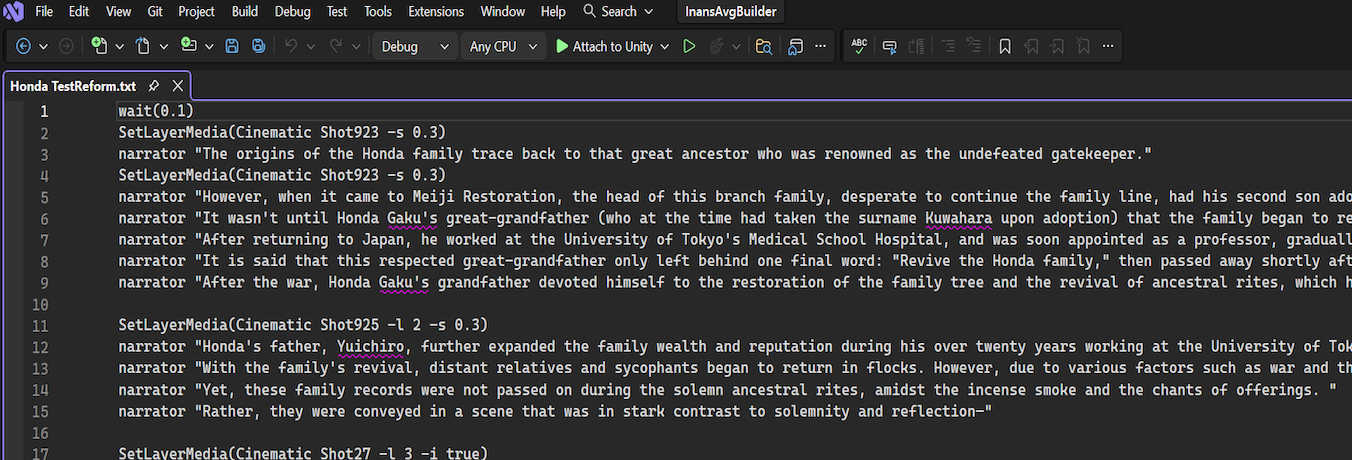

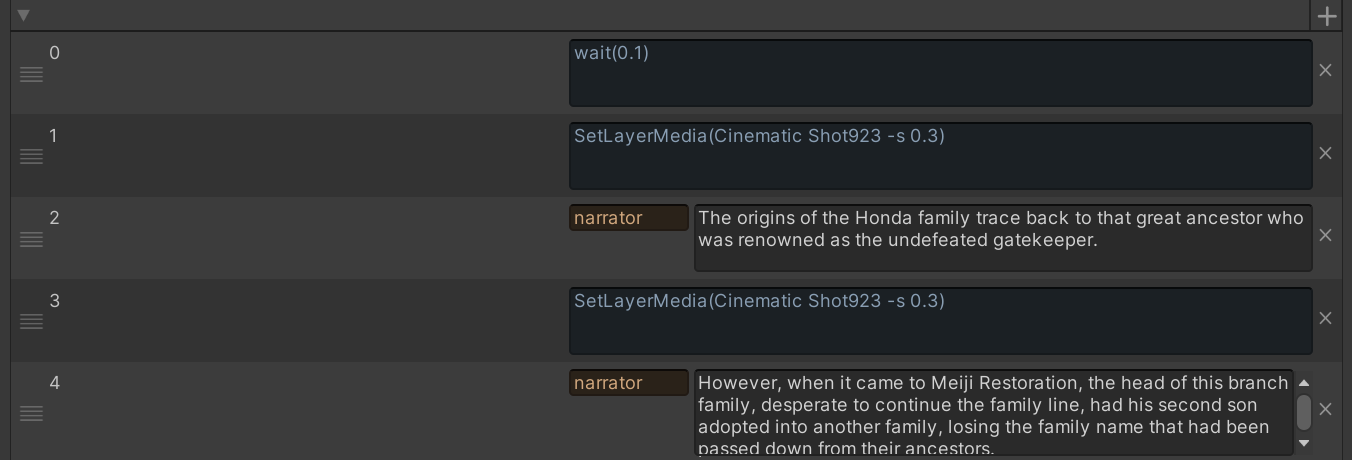

Obstacle 3: The "Black Box" Pipeline (Invisible Logic)

The Problem:

In the beginning, our development pipeline was essentially a "Black Box."

While the underlying system worked, it was not visualizeable. The complex narrative branches, variable changes, and character states existed only as abstract lines of code or disconnected data files.

This lack of visual feedback brought us endless nightmares:

- Tedious Work: Simple tasks required digging through multiple scripts.

- Hidden Bugs: It was nearly impossible to trace where a logic flow broke because we couldn't "see" the path.

- Creative Friction: As designers, we were spending 80% of our energy on implementation/debugging and only 20% on actual creativity.

I realized that we couldn't continue fighting our own engine. I decided to pause content production to refactor the pipeline and build a custom, Designer-Friendly Visual Tool.

- Visualizing the Invisible: I developed a node-based editor that displays the narrative flow, logic gates, and variable triggers in real-time.

- What You See Is What You Get: instead of writing abstract code, we can now drag, drop, and connect narrative nodes visually.

The Result:

This tool transformed our workflow. By making the system transparent, we eliminated the "guesswork" in debugging.

It turned a tedious, error-prone process into a smooth creative flow, allowing us to focus on what matters: the story.

Character Profiles

The refracted colors of human existence.

1. Natasha: The Meta-Vessel

Archetype: The Awakened / The Glitch

Existential Theme: Loneliness & Radical Self-Acceptance

(Explores the question: "Who am I if my existence is scripted?")

Design Overview: Natasha is the physical embodiment of the Meta-element. Her personality is deliberately designed to be "hollow," allowing her to function primarily as a vessel for the game's structural anomalies.

Key Conflict: The Ontological Crisis

- The Symptom: Natasha suffers from severe Cognitive Dissonance. Unlike other characters, she perceives the "programmatic nature" of the world. She sees the strings but lacks the vocabulary to describe them, leading to deep confusion and a sense of "wrongness."

- The Evolution (Node A): Under the guidance of Honda (the protagonist), Natasha undergoes a paradigm shift. She realizes her "symptoms" are not mental illness, but heightened awareness.

- The Resolution: She moves from confusion to Agency. She learns to accept her unique status as an entity that transcends the game's rules, eventually using this power to influence the narrative.

2. Yori: The Feral Catalyst

Archetype: The Outsider / The Wild Child

Existential Theme: Socialization as Self-Domestication

(Explores the question: "How much of my true self must I kill to belong?")

Design Overview: Yori is defined by Action over Words. Her cognition is closer to a feral animal than a socialized human. She represents raw, unfiltered instinct in a world of complex social lies.

Key Conflict: Friction of Perspective

- The Symptom: Yori operates on "Animal Logic." She cannot align her perspective with human social norms, creating constant friction with the world around her.

- The Incident (The Self-Exile): In the early game, Yori misinterprets a trivial social interaction as a "Threat" or "Fatal Error." Driven by a Fight or Flight response, she chooses to run away, exiling herself from the group.

- Narrative Function: She acts as the Catalyst. Her erratic, instinctual actions (often accidents) break the status quo and unintentionally create the opening for Natasha to take her first decisive step.

3. Tumugi: The Repressed Mirror

Archetype: The Perfect Victim / The Martyr

Existential Theme: Completion through Self-Destruction

(Explores the question: "Can I find wholeness by erasing myself?")

Design Overview: Tumugi represents Total Submission. She has fully internalized her family's oppressive arrangements, existing in a state of "Temporary Self-Consistency." She is unaware of her own suffering because she has repressed it entirely.

Key Conflict: The Phantom Scar

- The Symptom: Tumugi believes she is happy, but her subconscious screams otherwise. The conflict lies in the incompatibility between "Tumugi the Individual" and "Tumugi the Daughter."

- The Awakening (Node A): Through Honda's analysis of Natasha, Tumugi begins to see a reflection of herself. She realizes she shares a similar "abnormality."

- The Climax (The Tattoo): When Natasha exposes Tumugi's psychological files, the repression breaks. Tumugi gets a Tattoo—not for fashion, but to cover a "Phantom Scar" (a wound that exists only in her delusion). This is her tragic attempt to make her internal pain visible and tangible.

Retrospective: The Ghost in the Machine

Writing this post feels like archiving a memory. Goldfish was ambitious. Perhaps too ambitious. We tried to weave Existentialism, Psychoanalysis, and Meta-horror into a single narrative tapestry.

We built complex systems, fought through pipeline nightmares, and designed characters that were meant to question the very nature of their existence.

It hurts that we couldn't see Honda, Natasha, Yori, and Tumugi reach their final destinations. The project is frozen in time, a snapshot of who we were as developers at that specific moment.

But as I look at the Visual Tools we built and the Design Pillars we established, I realize that Goldfish didn't die in vain. It taught us how to structure complex narratives. It taught us the danger of unearned agency. And most importantly, it taught us how to survive the heartbreak of a team changing shape.

"The code is dormant, but the experience is alive. We are carrying these lessons into our next project."

Goldfish may be asleep, but we are just waking up.